As I prepare to celebrate the Fourth of July, I can’t think about the American Revolution without also thinking about what the colonists’ freedom meant for the indigenous people whose land they were taking, and specifically, the role that one of my Scots-Irish ancestors played in that colonization. Like many other Scots-Irish of the 1700s, he followed the Great Wagon Road, which was an established Indian hunting, trading and war trail, from Virginia into the frontier of North Carolina.

Scots-Irish as colonizers

In marking the birth of our nation, it is important that we acknowledge the history and legacy of colonialism. Even if we do not know the specifics of what our Scottish-American or Scots-Irish ancestors did, we do know that they were not native to this country. As early settlers, they took part in the removal, relocation, disbursement, concentration and forced removal of the people who were here before them.

Many of my ancestors were early settlers. On both sides of my family, I’ve been able to document those who were the “first” to settle a particular area — mostly in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee, which is the traditional territory of the Cherokee or the Ani-Kituwhagi as they call themselves. Arthur McFalls, my fifth great-grandfather, is the Scots-Irish ancestor about whom I have the most information pertaining to his interactions with indigenous people.

Uncovering the truth

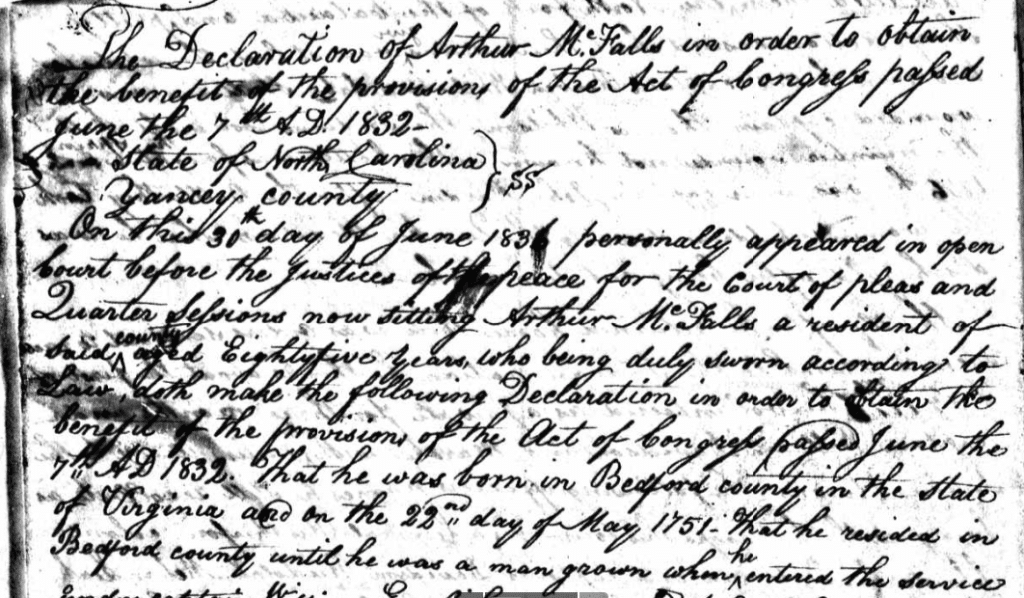

Arthur was born in 1751 in Bedford County, Virginia, and began his military service when he was “a man grown” with Captain William Inglis on the New River in Virginia. During most of his years of service, which I estimate to be from roughly 1773 to 1782, he served as an “Indian spy.” His battles were mostly with “hostile Indians” not with British soldiers and loyalists (though he was apparently on the wrong side at the Battle of King’s Mountain in October of 1780 — but that is a blog for another day!).

This information comes from Arthur’s declaration in 1834 and then another in 1836 as part of his Revolutionary War Pension Application; he was 83 when he made his first declaration. The colonial government enacted several different pension acts for service to the colonies giving full pay for life in 1832 to officers and enlisted men who served for two years or more and partial pay to those serving six months to two years.

Generally the process required an applicant to appear before a court of record in the state of his or her residence to describe under oath the service for which a pension was claimed. The application statement or “declaration,” as it was usually called, with such supporting papers as property schedules, marriage records, and affidavits of witnesses, was certified by the court and forwarded to the official, usually the Secretary of War or the Commissioner of Pensions, who was responsible for approving or rejecting the application. Some of these pension records are available today through the The National Archives and Records Administration.

The British use the Cherokee

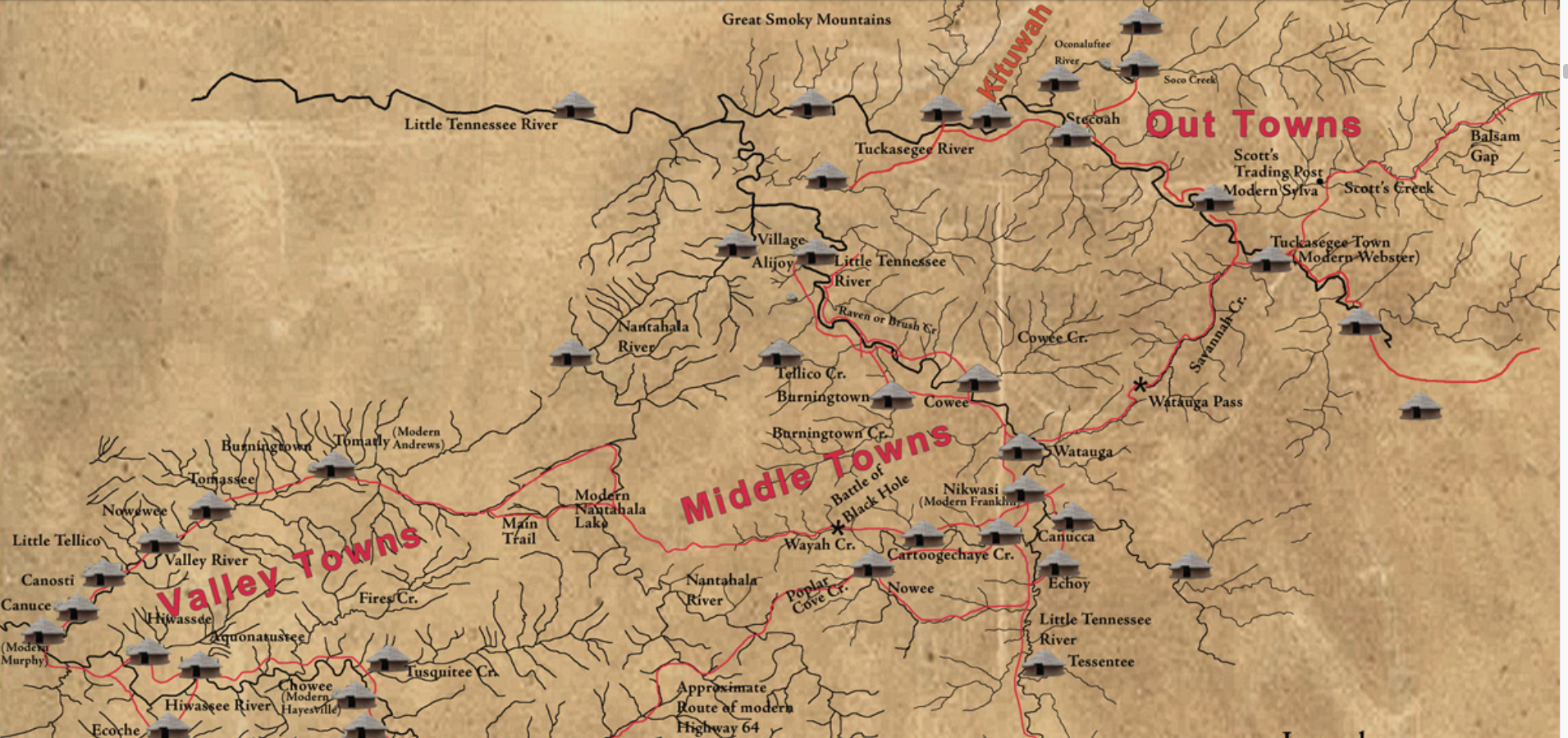

When the Revolutionary War began, the British, who had established a treaty with Cherokee as early as 1725, convinced the Cherokee to ally with them against the colonists with promises of securing their lands and stopping further colonization. British agents had repeatedly told the Cherokees they were fully within their rights to drive off squatters and seize their horses and cattle as a penalty for breaking the English treaty with the Cherokee. These violent conflicts between the Cherokee and the colonists took place in the frontier areas of Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina and Georgia in the southern Appalachian Mountains, the traditional territory of the Cherokee. They culminated in the Cherokee Expedition of 1776 in which my fifth great-grandfather participated.

The colonists respond with destruction

Here is Arthur McFalls’ account of the colonists attacking Cherokee towns, specifically Watauga, which is near current-day Franklin, North Carolina:

(NOTE: Arthur’s statement was recorded by a clerk in open Court before the Justices of the Peace for the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions of State of North Carolina, Yancey County in June of 1836. In the interest of space, I have not included portions of his declaration where he lists the names of officers or other soldiers with whom he served.)

“About the first of July 1776, he volunteered as a private for three months under Captain William Davidson and marched with the main army to the Indian towns. …After they marched over the Swannanoa River he was appointed and sworn in as an Indian spy… That the spies marched about three quarters of a mile before the main Army with orders to give no false alarms and keep a good look out for Indians and Indian signs. That at the Tuckaseegee Gap the Indians fired upon the spies and wounded William Alexander, and Joseph McDowell wounded an Indian. Soon after passing this gap, they entered the Indian town Watauga which they burnt and destroyed the corn and potatoes. That he was marched as far as the Valley towns, that they burnt about seven towns and cut down and destroyed the corn and potoes [potatoes]. Killed some Indians and took some prisoners and two white men found among them and gave them all up to the South Carolina troops under General Andrew Williamson. And we brought in General Williamson’s wounded — they lost some few men killed and had some wounded but was not in any close engagement. At the expiration of his term of service, he got his discharge in Burke [County].”

According to the Museum of the Cherokee Indian, more than 36 Cherokee towns were destroyed; some accounts of the Cherokee War of 1776 estimate up to 56 towns were burned to the ground. The attack devastated the food supply of the Cherokee, and shortly afterward, they began signing treaties with the colonial government giving up large portions of their land.

More murder and mayhem

Arthur’s role as an Indian spy continued for many years as the Cherokee also continued their fight against colonization. In his 1834 pension declaration Arthur states that in 1781 he volunteered again into the service for nine months and was stationed at Wawfords [Woffords] Fort in Turkey Cove in Burke County where he was again sworn in and served as an Indian spy.

“That he shot and wounded an Indian while out spying. That the Indians killed two men and wounded and scalped his wife near the fort and left her for dead — and soon afterwards attacked the fort and killed Edward Lee and wounded Jesse Halley and shot the button off the waistband of the Applicant’s bridges [breeches]. The same night they started a man to the fort on the Catawba for a reinforcement but the Indians ran him back to the fort. They then mounted the Applicant upon a horse and he ran through the enemy without receiving any injury and arrived safe at the fort where he obtained a reinforcement and returned with them the next day, when the Indians fled.”

While Arthur’s wife, Mary Jane, did not die from the attack, there is some evidence (a letter from her brother to Arthur, which has not been verified) that Arthur left her because she was disfigured from injuries sustained in the attack. The letter also thanks Arthur for killing the Indians that attacked Mary Jane and forgives him for leaving her. Other sources, also unverified, say that when Arthur left Mary Jane he began living with an “Indian lady” by the name of Teakena. She and Mary Jane are buried in unmarked graves near Arthur in the Grassy Creek Baptist Church Cemetery in Spruce Pine, North Carolina.

Truth and reconciliation

Arthur is not an ancestor of whom I am proud, but he is a part of my family’s history. And his life helps me understand the complicated interactions and relationships the early settlers had with the indigenous people. Some would say that Arthur was only defending himself and his family against atrocities inflicted on them by the Cherokee and other indigenous people. But he was part of a colonizing force. It doesn’t matter that his family, his neighbors and other settlers may have been escaping trauma in their homeland of Scotland or the Ulster Plantations in the north of Ireland. They were the aggressors against the people who were here first.

As you celebrate Independence Day as a Scottish American or Scots-Irish American, I encourage you to learn about and acknowledge the indigenous people who lived where your ancestors settled. A good place to start is the Native Land website or app (for both iOS and Android); just put your address into the search box, and you’ll be able to see what indigenous people once lived there or nearby.

For my Fourth of July celebration this year, I am committing myself to learn more about the impact of colonialism as it relates to the Cherokee territory in the Southern Appalachians, especially in the Great Smoky Mountains where I grew up. This blog is a first step in acknowledging that my ancestral home was originally the home of the Cherokee and that my ancestors took their home away. To recognize and honor the culture of the Cherokee, I am making a donation to the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, North Carolina, home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and to the Cherokee Heritage Center of the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

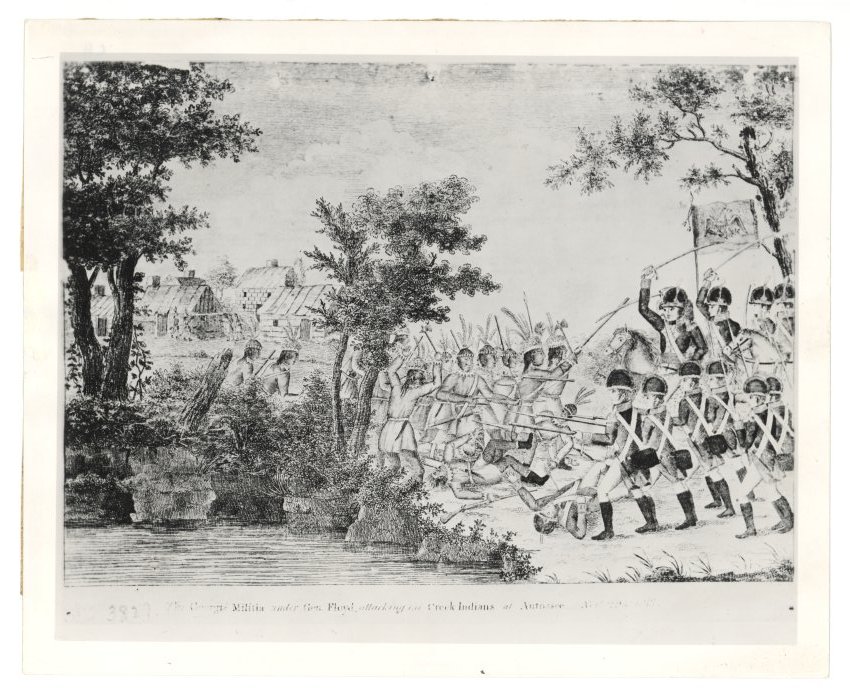

Featured photo credit: Creek war scene with Indians defending their village against American soldiers in the War of 1812. (Photo Credit: American Heritage Picture Collection). Scene also featured in Museum of the Cherokee Indian Exhibit.

3 Comments

Very well written and very informative.

Well done

Hello Diana. I was recently researching exactly WHAT the heck Scots-Irish is, and means. I do have Scots-Irish ancestry with 29% of it Scottish and 11% Irish. My ancestral heritage is of course from the north and central Ireland. I am grateful for finding your well written and documented blog post. As I was researching Scots-Irish history, I was appalled to realize my ancestors would have been colonizers. (I do not know what I was expecting) Anyway, it is difficult to reconcile with this history, and I appreciate your blog post.

My husband David Van McFalls is related to Arthur