As I prepare to help host a Clan Chattan tent at the upcoming Grandfather Mountain Highland Games, I am thinking about what my answer will be when people ask how to determine if their ancestors were part of a Scottish clan. Typically, I would tell people to pick a family surname and research its origin. There are a number of online sites where you can do a quick search to learn if your name is associated with a Scottish clan.

For many Scottish Americans or Scots-Irish Americans that is enough. Knowing that a family surname has Scottish roots and that there is a clan and a tartan satisfies their curiosity. Others want to trace their heritage through the generations back to Scotland. Among those folks who join clans, host clan tents, attend Scottish highland games, wear kilts and drink wee drams, you will find both kinds of people.

The proof is in the DNA

I am the “need to trace it back across the pond” kind. My mother and I have been working to establish the ancestral connection from our American McFalls to Scottish MacPhails. Since I first wrote about my Scots-Irish ancestor Arthur McFalls in February 2020, my mother has connected with descendants from nine of Arthur’s 10 children (with three different women). To help unravel the question of which descendants went with which wife, we started an Arthur McFalls ancestry group on Facebook. The group currently has 133 members; most of whom are descendants of Arthur, though some are likely descended from relatives of Arthur who immigrated around the same time. We have also connected with some Scottish cousins who are helping put together the story of the McFalls/MacPhails before they immigrated to the Colonies. Slowly we are piecing together the story of many of the McFalls in the United States as well as their common ancestors in northern Ireland and Scotland.

Arthur McFalls was born in the Colony of Virginia in the mid 1700s. We think that his father or grandfather were the first generation immigrants to the colonies along with several other family members coming from what is now Northern Ireland. Because we weren’t getting anywhere with paper records, we began exploring Y-DNA testing with the help of two male relatives. After doing several versions of Y-DNA testing (which looks at paternal lineage), we finally decided to spring for the Big Y-700 test, which explores two types of genetic markers, one for recent DNA connections and another for distant ones.

What’s in a name?

We’ve encountered many surprises along this journey of discovering our Scottish ancestry, so it was really not a huge shock when the Y-700 DNA test revealed that we were Mcleans. Yep. Not McFalls, not MacPhails. Our paternal lineage was Mclean.

Potentially, with Y-DNA testing you can discover your ancient ancestral origins because all males descend from a single male ancestor. But establishing that lineage requires DNA samples from lots and lots of men. If you start with more recent history, say 1,000 years ago around the time surnames came into use, then your Y-DNA can tell that you were hanging out with a tribe of people who eventually called themselves Mclean.

I don’t know statistically how common it is for people who do the Y-DNA testing to discover that their paternal lineage is not what they thought. In our McFalls ancestry group, it’s happened a number of times. In trying to find the ancestor/s who immigrated to the colonies, my mother has asked some of the male McFalls in our Facebook ancestry group to do the Y-700 DNA test. To date, six males (out of 133 total members in the group) who have taken the test learned that their paternal ancestral surname is not McFalls/MacPhail.

For some the results were quite unexpected. Others already suspected that even though their paternal surname was McFall/s, their connection was a maternal one. All of them are still McFalls – just not paternally. Perhaps this is also the explanation for our McFalls surname. My mother and I hypothesize that at some point in our history, our male Mclean ancestor impregnated a female MacPhail ancestor. Maybe he took her name. Maybe they had a child out of wedlock. Or maybe she was raped, and the baby was raised as a MacPhail. That’s something we will likely never know. But it is part of who we are as McFalls. We do know that when our ancestor immigrated, likely in the late 1600s or early 1700s, his name was McFalls. Some amateur genealogists have told us that the McFalls name likely came into use in the 1600s in what is now Northern Ireland.

Don’t get stuck on it

Our focus on male surnames can actually be a stumbling block when researching the full story of our Scottish heritage. Chris McLain, administrator of the Gallowglass Project on FamilyTreeDNA (apparently our Mclean/MacPhail ancestor was part of this mercenary group in Ireland but more on that in another blog!), had this to say in a comment on the feed for the group:

“The rigid father-to-son passing of surnames that our anglicized minds are all accustomed to is a very English thing. The crosscurrents of Gaelic society like social status, fosterage, and broken genealogies (i.e. the “raping and pillaging” factor of neighboring clans at war causing non-paternal events in each other’s populations for a thousand years), the presence of “bastard-sons” conveniently kept hidden to pass land and title (especially true if a line was about to “daughter-out”), plus the ebb and flow of territorial disputes where native populations took a new clan landlord’s name for protection, may have folks comfortable with their accepted lines of descent on paper unwilling to swab their cheeks and find out something contrary. The overwhelming majority of us simply *acquired* this surname one way or another between 1300 and 1800. However I think it’s more important to find who your greater kin really are than what your surname ended up as when English society of taxes and censuses intruded on your ancestors’ way of life. Your paternal line’s surname could have changed three, four, or even more times since Gaelic patronymics began developing in the 11th century.”

The good, the bad and the ugly

If we are open to fully exploring our heritage, we must accept all of it because we can’t change it. We should acknowledge that our Scottish American and Scots-Irish ancestors were colonizers and enslavers, but it’s also true that they themselves may have been escaping dire circumstances in their homeland. As melting pot people, we can keep exploring those ancestral connections while knowing that our clan can truly be who we choose.

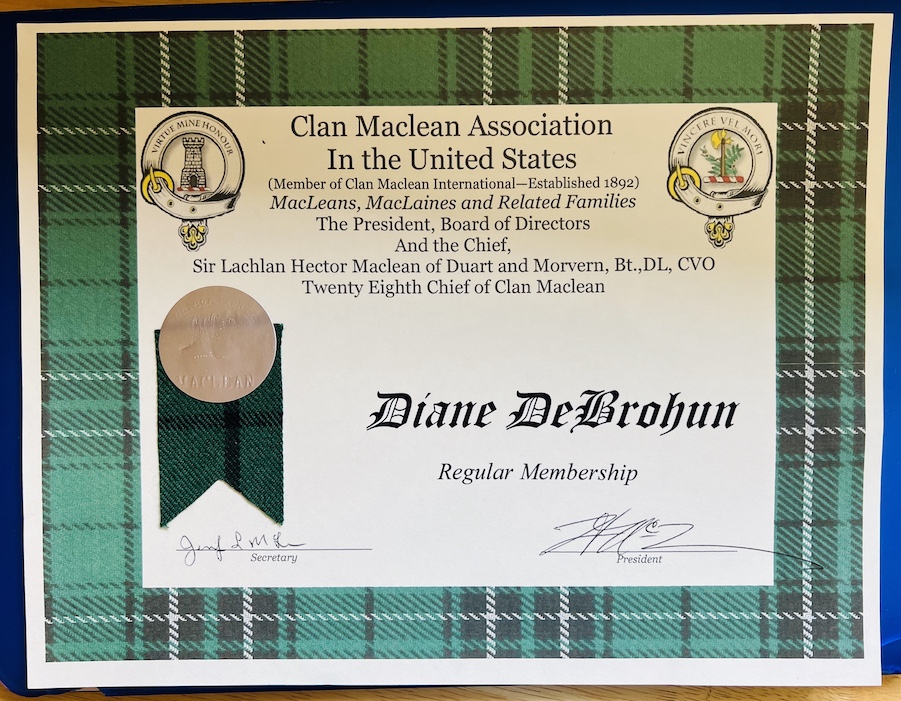

Because I wanted to know more about my newly discovered Mclean kin, I officially joined the Clan Maclean Association in the United States. I now have a lovely membership certificate (on which my name is misspelled, but what’s in a name!), a membership pin and lots of great info about Mcleans in the United States. In the meantime, I’ll still be representing Clan MacPhail, along with another MacPhail and some McFalls, at the Grandfather Mountain Highland Games. Since the MacPhails and the Macleans were part of Clan Chattan, I’m keeping it all in the family!

4 Comments

Hi Im Kelly. My brother has traced us back to great, great, great Landon Hamilton buried at Gettysburg. Also that our Hamilton clan settled in Catawaba, North Carolina. Many Johns…John Garland Hamilton I through III.

Very informative blog, thank you for sharing.

My Mothers father was a Dunbar from County Cork. Her Mother was a Mathers from County Armagh, and Thompson

My father’s father was Norwegian who took the surname apparently from Scotland. His mother was a Gilroy (MacGillvray)

So I am your basic Northern European mongrel.

Very interesting. I, too, am connected with a y-dna study, managing one account and staring at others. Finding missing names appears unlikely the more I and others learn about y-dna, but finding common distant ancestors may one day lead to some breakthroughs. Maybe not in my lifetime, but one day…