We Scottish Americans love our tartan, and wearing tartan is an excellent way to embrace our Scottish heritage. Unfortunately, we are often less inclined to learn and embrace the somewhat confusing history of the Scottish tartan.

What is tartan?

Tartan is a woven material, generally of wool, having a pattern of interlocking stripes of different breadth. All woven fabrics are made up of the warp — the threads that are stretched out lengthways on a loom — and the weft, the threads that are interwoven with the warp at right angles to it. A tartan’s sett is what makes it unique. This is the thread count that defines it — the sequence and number of colored threads that produces a tartan’s distinct look when woven in criss-crossing vertical and horizontal stripes. In the United States we might call tartan plaid, but in Scotland a “plaid” is a blanket of sorts. The Gaelic for tartan is breacan, meaning speckled, striped or multi-colored.

How long have tartans been around?

According to the Scottish Tartans Authority, a Scottish nonprofit dedicated to the preservation, promotion and protection of tartan, the Celts have been weaving tartan for at least 3,000 years. In documents dating back to the 12th century there are numerous references to tartan and plaid fabric being worn by individuals in what is now Scotland. But the look of tartan in those days was likely determined by the local weaver — not a clan.

In order for a tartan to have its distinctive colors, the yarn must be dyed. Traditionally, local dyes were made from natural indigenous products. Early tartan reflected the local flora used for dyes rather than a design determined by a family or clan. Because clans were also geographically based, local weavers would likely have produced a similar tartan for members of that clan.

Tartan and the Jacobites

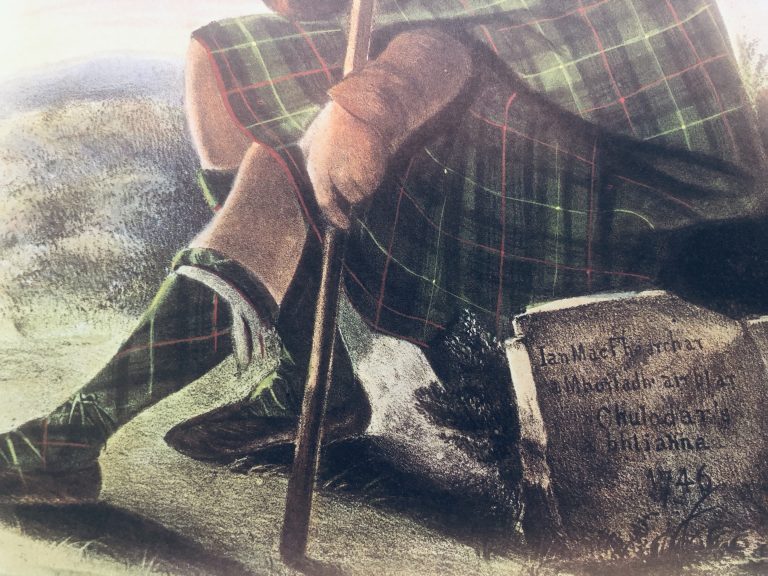

While there are some legitimate origin stories for clan tartans prior to the 18th century, tartans as we know them today — those that are identified with a family name or a clan — developed primarily in the 19th century. A number of historic events influenced why and how this happened, including the 1746 battle of Culloden, the last of the Jacobite rebellions that had started in 1745. The Jacobite Rising was an attempt to restore the House of Stuart, represented by Charles Edward Stuart, to the British throne and an objection to the union of Scotland and Great Britain. Often portrayed as a battle between Scotland and England, some claim there were more Scots fighting against Bonnie Prince Charlie than for him.

After the Jacobites were defeated, Great Britain passed the Act of Proscription, which included a ban on wearing “Highland dress.” This attempt to incorporate Scotland, especially the “barbaric” Highlanders, into the United Kingdom reserved the right of wearing tartan kilts and plaids only to soldiers and officers in the British army and landed gentry.

Within a few years of Culloden, Highlanders were being recruited into the British army with the promise of a wage and the ability to wear the “garb of Old Gaul.” With little economic choice, many fought for the British Crown in order to survive. Their success as soldiers of the Crown endeared them not only to Scots but also to Great Britain, and in 1782, the Act of Proscription was repealed. With the passing of 36 years, tartan was no longer a part of everyday Highland clothing — though its use as military dress for Scottish regiments became firmly established.

Introducing the romantic tartan-wearing Highlander

Another event that helped to rehabilitate the tartan-wearing Highlanders in the view of those outside of the Highlands was the works of Scottish novelist, Sir Walter Scott. His first novel, Waverly, came out in 1814 and was a highly romanticized version of the “Forty-Five,” the Jacobite rebellion starting in 1745. It met with considerable success, and Scott followed it with a series of novels over the next five years that idealized the Highland way of life. Scott’s readers south of the border in Great Britain knew very little about their northern neighbors and were greatly captivated by his stories. His audience included King George IV and later his daughter, Princess Victoria (Queen Victoria). With a royal following, Sir Walter Scott’s works soon became quite popular, and Great Britain fell in love with all things Highland and tartan.

In 1822, Sir Walter Scott was asked to organize the visit of King George IV to Scotland, the first such visit of the sitting monarch since 1651. Scott applied the same romantic and idealized notions of the Highlands from his novels to the pageantry and staging of events around the king’s visit. For the grand Highland ball in honor of the king, Scott instructed that all gentlemen in attendance, if not in uniform, should wear the “ancient Highland costume.” This created what some refer to as the 1822 “tartan rush” as Highland and even Lowland (who traditionally didn’t wear tartan) aristocracy sought to have a family or clan tartan made for the big visit.

Tartan becomes part of Scottish identity

By this time, the weaving of tartan was done in mills — not by village weavers. While the mills had records of specific tartans, they were identified by numbers — not clan names. So imagine a clan chieftain showing up at the mill and asking for yardage of his “clan” tartan in preparation for the king’s visit! In some cases, the chief may have had a scrap of tartan fabric as an example for the mill. But in most cases, he was shown samples of tartan and simply picked what he liked!

John Murray, the 4th Duke of Atholl, later described the king’s visit as ‘one and twenty daft days’ and noted in his journal that: “The Mania is the Highland garb . . . a considerable Procession of Troops, Highlanders and the different Persons dressed up by [Sir] W: Scott in fantastic attire.”

During his visit, King George IV wholeheartedly embraced Sir Walter Scott’s Highland pageantry, wearing a kilt of bold red tartan that some claim to be what is known today as the Royal Stuart (or Stewart) tartan. The royal interest in and acceptance of all things Highland, along with Sir Walter Scott’s works and the use of tartan for Scottish regiments fighting for the Crown, all combined to cement the tartan’s place as a fundamental part of Scottish identity — even though it was originally only worn in the Highlands and Islands.

Next, modern-day Scottish Americans live their heritage through wearing lots of tartan.

4 Comments

Well done Diana!

Thank you!

It’s also so interesting just how many clan tartans are modeled on the regimental Black Watch, which preceded the individuals clan setts. There are, naturally, small and subtle distinctions (a yellow stripe there, a red or white stripe added there), but if you put the Campbell Old, the Gordon Weathered, the Munro Hunting, the MacLachlan Weathered, the Lamont Ancient, the MacKenzie Weathered, the Fraser, and the Grant Hunting (and probably more I don’t know of) side-by-side, they are clearly all drawing from a similar pattern.

Great article and enjoying your site.

Touch Not the Catt Bot A Glove!

Hawk

Very interesting! And very informative!